Works by Asel Kadyrkhanova

St(itching) Silence – A Creative Response to Asel Kadyrkhanova

28.04.2023

Poet Cheng Tim Tim responds to Asel Kadykhanova’s works, Soz Joq/ Speechless and Marijam (Names of my grandmothers), exhibited in CHAT Spring Programme 2023.

I enter this room before I know I am looking for you. Unlike history, every exhibit here is intentional and within reach. I am convinced that the harder I look, the more I will get to know you. But how uncomfortable that is—to put your suffering on display, to watch it on repeat because I need the story. How do I resist the urge to narrate one of us into the ghost of ghosts?

…

Harsh echoes from the other side of the room draw me away. Clang. Clang. Clang: figures, adorned, in parallel, are fighting their own apparition. Conflicts as a feedback loop, their patterns foretold in syrmak carpets.

On the adjacent wall, a large red felt panel—edged with sequins and silk from Hong Kong’s discontinued factories, studded with pins—casts Kazakhs’s shimmering, post-nomadic shadows.

Slightly off the centre of the room, flat ornaments expand into three-dimensional space: a door woven with fairy tales in bold strokes leads to a door of double-layered, cut, sacral symbols, behind which a party light projects technicoloured blobs that swirl and swirl.

Works by Gulnur Mukazhanova (left) and Bakhyt Bubikanova (centre and right)

Works by Gulnur Mukazhanova (left) and Bakhyt Bubikanova (centre and right)

I keep making way for other visitors so that I do not block their field of vision. But I find myself returning to you time and again, greedy for meanings. I seek what must be remembered in what cannot be remembered. I seek the hurt in inheritance. I seek language.

…

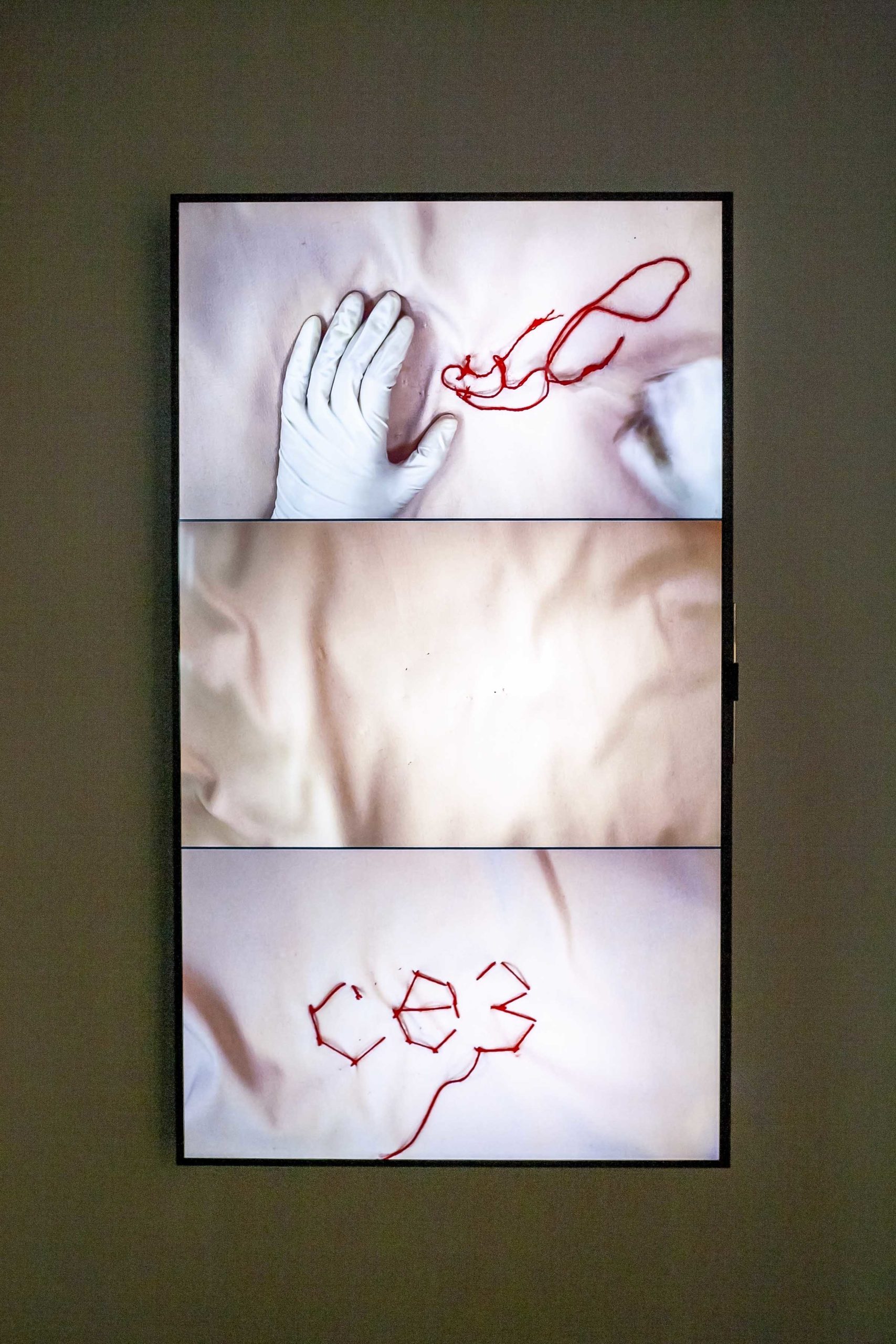

Two hands in latex gloves unstitch a thick, red thread from a pale, skin-like fabric. As one forceps-holding hand operates its abrasive procedures, the other hand fixes the twitching cloth. In the middle frame, the hue is warmer and older. There is no hand, no thread, almost no trace left. On closer look, though, pinholes remain alongside unsmoothed creases. In the last frame, three letters lie disjointed, coarse. A loose thread extends out of sight.

Do not walk away just yet. Stay and see such erasure and its reversal: stitch, unstitch, stitch, unstitch over and over again.

Asel Kadyrkhanova, Soz Joq / Speechless, 2017, updated 2022

Asel Kadyrkhanova, Soz Joq / Speechless, 2017, updated 2022

How description puts in order what the naked eye cannot bear. Each of the three frames stands for alphabets given and taken from Kazakhs during Sovietisation. No words in Arabic scripts. No words in Latin Yanalif. No words in Cyrillic. Soz Joq, Soz Joq, Soz Joq in a decade of famine and purges. How many books became unreadable? How many lost a common vocabulary, illiterate for each other? As bodies carry strands of pain, a red thread twirls and unspools by way of witnessing.

…

To seek you is to embody silence, to acknowledge a disjuncture in our lineage. I seek in textile an unspeakable text, words unsaid by people I have never met, a testimony that has yet to take shape.

…

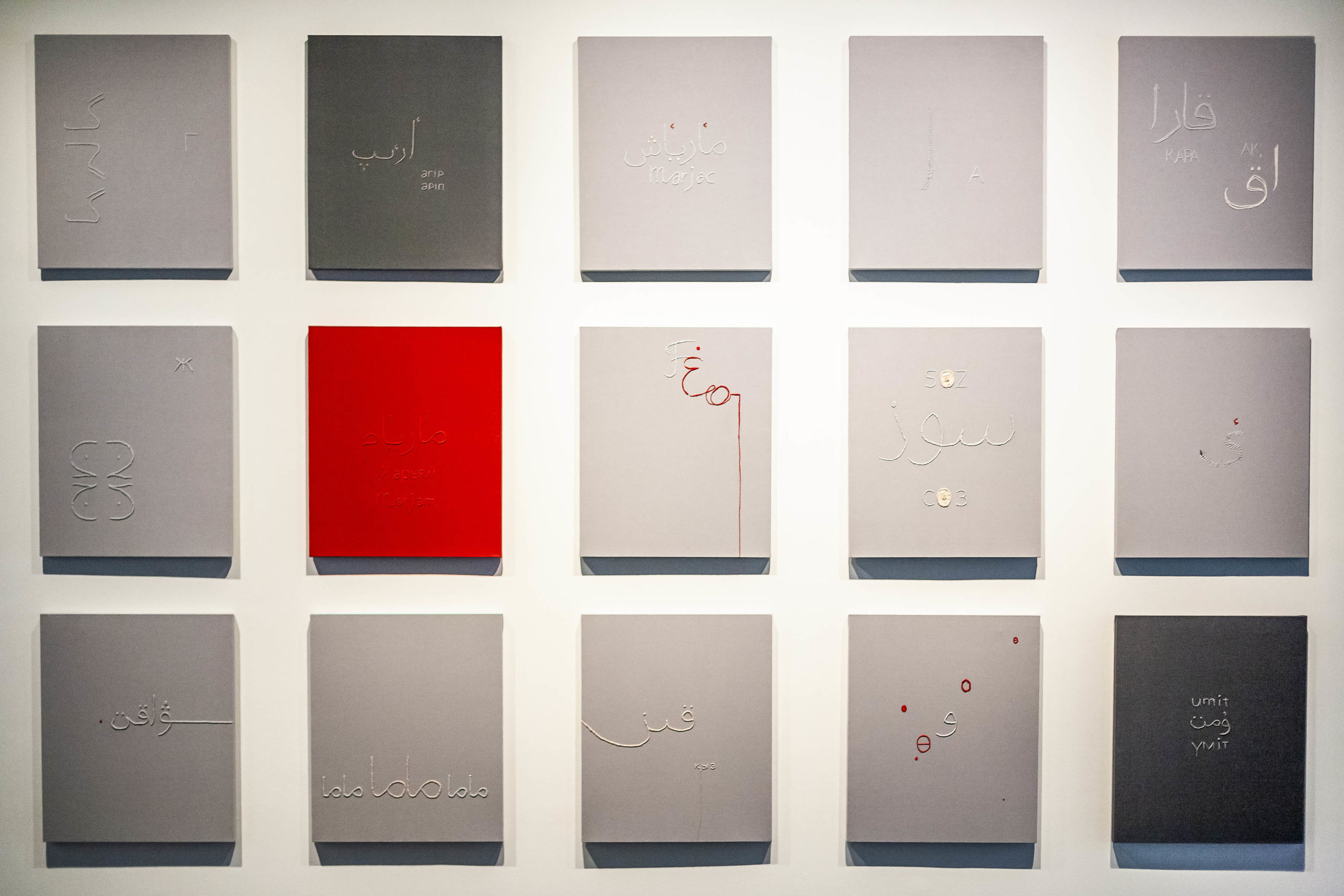

Next to Soz Joq / Speechless, 15 canvases hang solemnly, neatly on the wall. From afar, most of them seem empty. One red canvas stands out among 14 shades of grey. I struggle to view them. They are much higher than my eye level. I step closer. Each panel is sparsely embroidered with words I cannot read, with threads of a colour that fuses into the background. Grey on grey. Occasional red and white pops as my unlearned eyes travel along these tightly knitted lines and dots and circles.

Asel Kadyrkhanova, Marijam (Names of my grandmothers), 2022

Asel Kadyrkhanova, Marijam (Names of my grandmothers), 2022

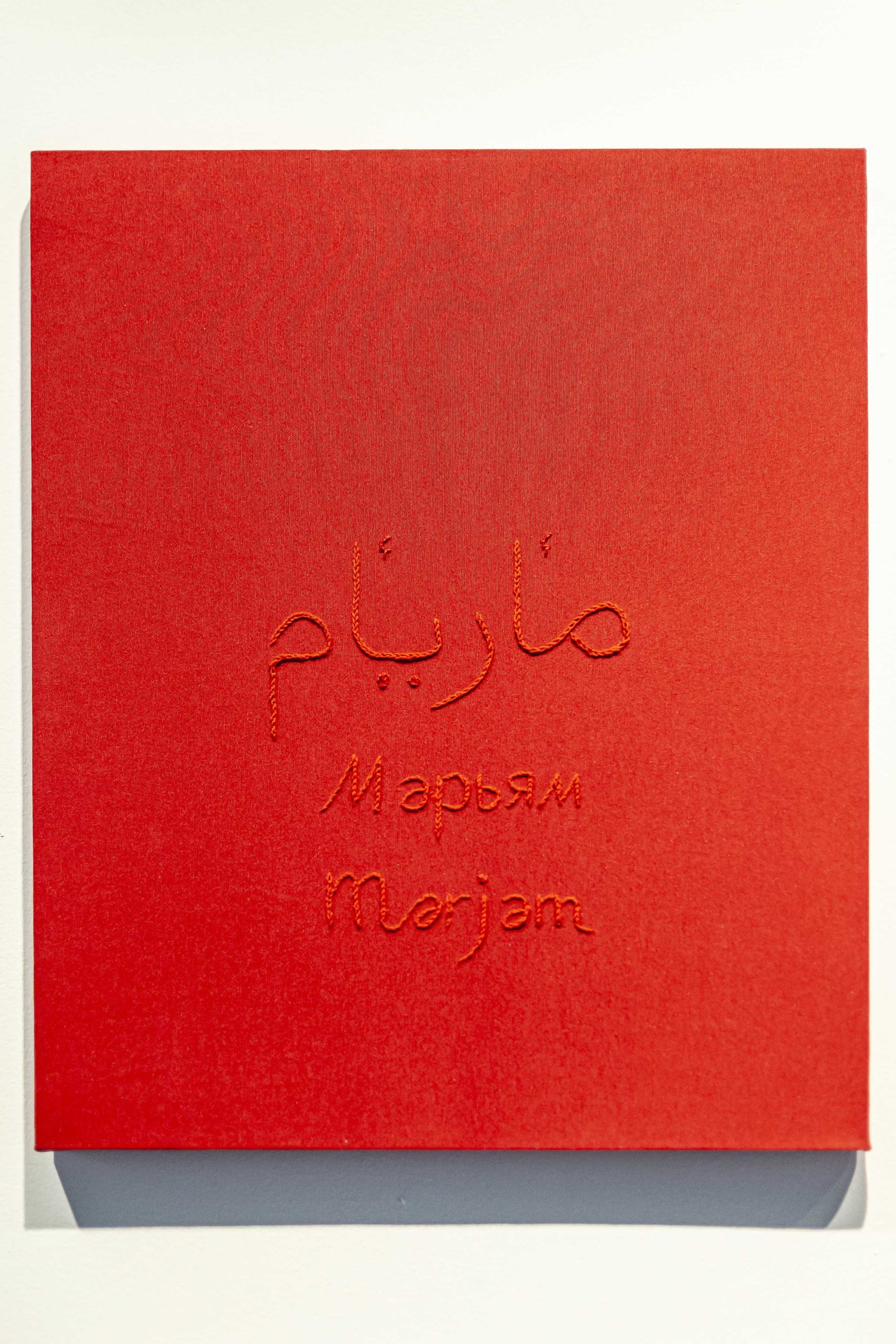

In this sequence of exercises called Marijam (Names of my grandmothers), every stitch feels like a scar. Before meanings take place, signs supersede. Scripts undulate, proceed unfinished, plunge, bubble away in various positions. However brief a word is, moving it from mouth to hand to fabric prolongs it. Mәrijәm, Mәrijәm, Mәrijәm—To weave a grandmother’s name in languages she regretted not grasping is to reclaim one’s stand within traditions. Pass on the tambour technique from grandmothers to mothers to daughters. Depart from the palette of ornamental contrast. Centre this absence, red on red.

Marijam in three scripts; Asel Kadyrkhanova, Marijam (Names of my grandmothers), 2022 (Detail)

Marijam in three scripts; Asel Kadyrkhanova, Marijam (Names of my grandmothers), 2022 (Detail)

…

I must admit that I cannot see you without superimposing what comes before our encounter. You conjure an image of my great-grandmother: In bed, she wets a thread in her mouth to make its split ends stick. When she cannot pull the thread through the eye of the needle, she asks for my help. She is always mending her shirts. When she ties the last knot and finishes the last stitch, she bites the thread instead of cutting it with scissors. I only know the Chinese name of my great-grandmother, who was born with an Indonesian name. If I dive into documents, will these voices from rooms I have never lived in tell me what I need?

…

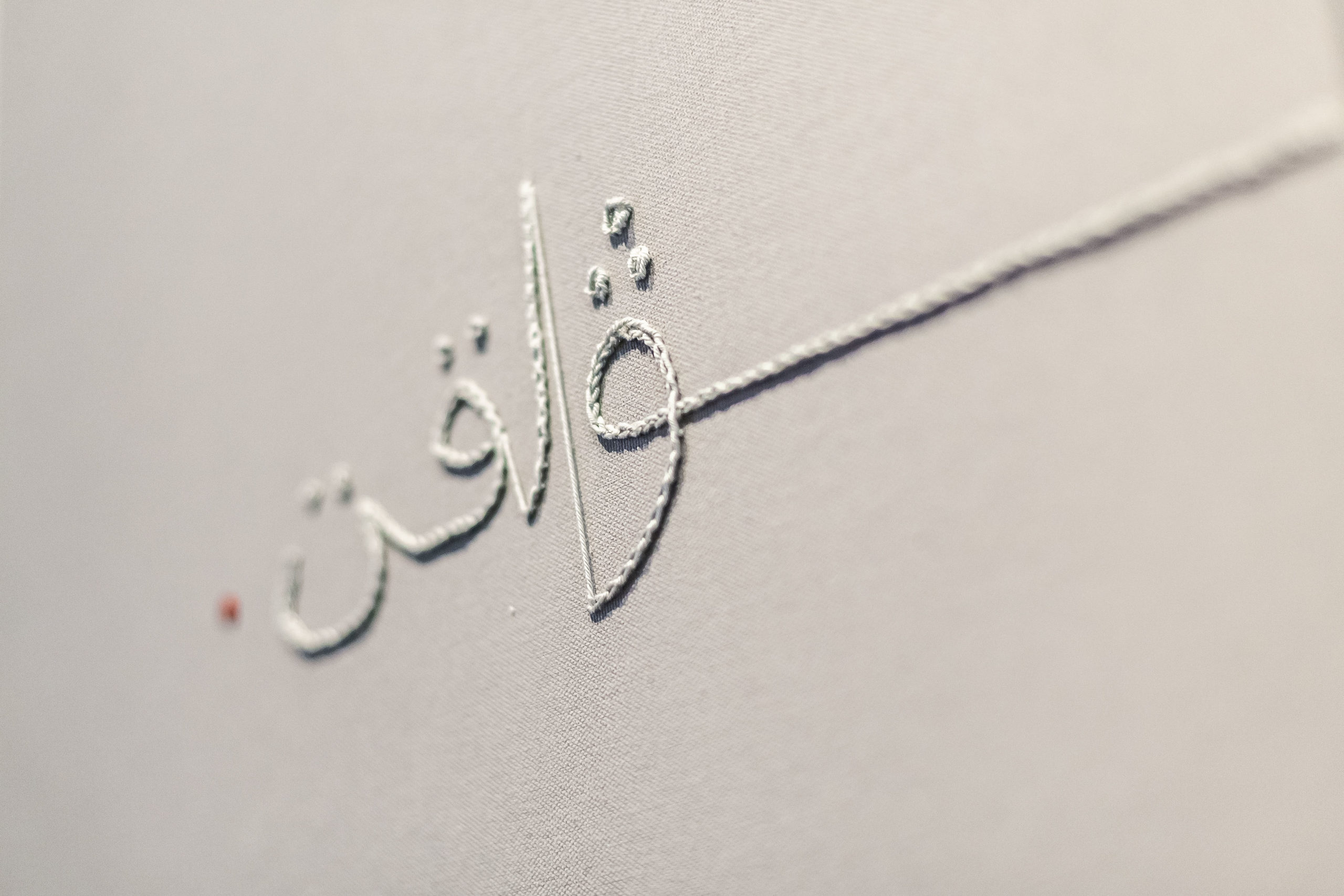

What is the past’s favourite story to tell: The beginning or the end? I have devoted myself to slow down the past, word by word. I pick up fragments woven by women as the world continues its careless spin. Black… hope… time… girls… in silence, our lives braid a text—unseen, dignified, omnipresent.

Time in Arabic; Asel Kadyrkhanova, Marijam (Names of my grandmothers), 2022 (Detail)

Time in Arabic; Asel Kadyrkhanova, Marijam (Names of my grandmothers), 2022 (Detail)

Clouds, Power and Ornament – Roving Central Asia is exhibiting until 21 May, 2023.